|

Donald Sterling’s recent, very racist comments, have thrown the NBA into disarray in the midst of an exciting playoff season. There are so many responses to this story ranging from: what the players should do in protest, calls for fans to boycott games at the Staples Center, a focus on a supposed violation of Sterling’s first amendment rights, and an obsession with the motives of Sterling’s girlfriend. However, the sole focus at this point should be on the NBA and its response to this crisis.

This was not the first time that Donald Sterling espoused or did something racist. In fact, he has a long, documented history of racial offences, all of which the NBA was aware of. David Stern, long-time NBA Commissioner who retired in February, has dodged an almighty scandal that is largely of his own doing. Now, his successor Adam Silver, is tasked with cleaning up a mess that he didn’t necessarily create. Why, when Stern and all of Sterling’s owner colleagues knew who he was, are we only now at a point where this is being dealt with? I have to believe that David Stern and his cronies felt that there was too much money to be made without the disturbance of a race scandal. Stern was no stranger to dealing with race during his time as NBA Commissioner. Navid Farnia at Over The Line has done a superb job of capturing the lengths to which Stern went to “whitewash” the NBA in order to make his league more marketable, or less threatening, to white audiences. His dress code policy, implemented prior to the 2005-2006 season, was an attempt to have the players look decidedly less “thug” and more “businesslike.” It was a direct target at players who fashioned a more urban aesthetic: chains, shorts, indoor sunglasses, T-shirts, jerseys etc. If Stern had to deal with black players, at least he was going to make sure they carried themselves in a more “civilized” manner. The plantation metaphor fits his iron rule of the NBA like a glove. Stern has always been concerned with the "image" of the NBA, which necessitated actions against its mostly black players. Yet, if he were truly concerned, from a moral standpoint, he would have levied sanctions against Sterling when any of his previous transgressions came to light. When there are so many moving parts to a story, and a multitude of interested parties, it can be difficult to focus on the issues that matter most and hold the right people accountable. Donald Sterling is the obvious choice as far as culpability, but the NBA is his joint defendant in this case for decades of inaction and willingness to do business with all manner of unsavory types, all in pursuit of the almighty dollar. Adam Silver may issue a punishment to Sterling tomorrow, and it may satisfy most of the people hurt by this saga. Yet, David Stern is deserving of judgment that he will likely never receive. That is one of the real shames of this story. He fostered a hostile environment toward black culture in his NBA that was in keeping with Donald Sterling’s belief system. David Stern allowed this to happen. As for Donald Sterling, let’s move past any temptation to feel sorry for him. Regardless of how this current scandal started, we know with certainty, that he is a racist, a bigot, and overall abhorrent human being. And what is the worst that could happen to him? He bought the Los Angeles Clippers in 1981 for $12.5 million. Should he be forced to sell the team because of this scandal, he stands to make over $500 million in profit. Meanwhile, the Los Angeles Clippers are tied 2-2 with the Golden State Warriors in a best-of-7 first round playoff series. They suffered a blowout in their first game after the scandal broke, and coach Doc Rivers cancelled practice on Monday so that the players could spend time with their families. Who can say how much these players are hurting? How can they put this behind them mentally and carry on with the rest of the series? This is the most immediate reason for Adam Silver to act swiftly and decisively. The NBA needs to move beyond the modus operandi of David Stern and take a stand for its players. It’s also a chance for Adam Silver to make a claim for his NBA, and the type of league he intends to oversee. Forget the league's image, the players need Silver to do the right thing.

2 Comments

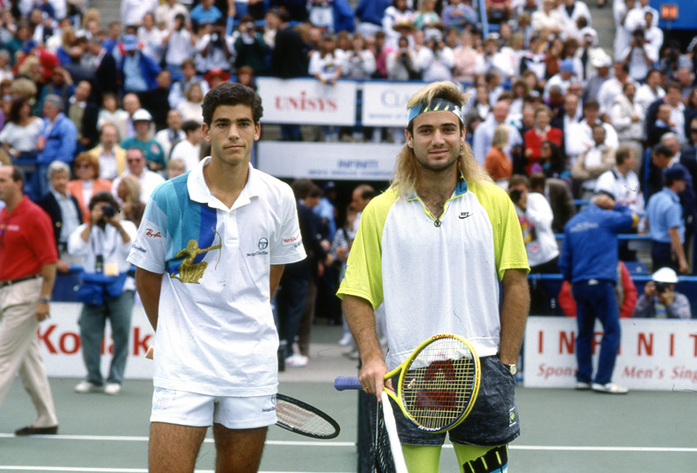

Pete Sampras and Andre Agassi were kings of the ATP Tour in the 1990s. Their reign coincided with a boom in American men’s tennis, and their rivalry was that era’s exclamation point. It came on the heels of McEnroe-Connors, ensuring a decades-long presence of American men at the penthouse of the ATP Tour. Pete and Andre were part of a very special class of American tennis players who emerged at the turn of the decade. By 1994, Michael Chang, Pete Sampras, Jim Courier, and Agassi were all Grand Slam champions, and even though Courier reached #1 and won four Slams, it was Sampras and Agassi who were the top dogs of that great generation. They were a marketer’s dream: opposites in all the right ways to form one of the greatest tennis duos of all time. Agassi possessed the flash, a walking embodiment of Nike’s “Image Is Everything” campaign. He wore the brightest colours, sported a ponytail, and openly flouted the tennis establishment; he chose to skip Wimbledon between 1988-1990 because of the tournament’s all-white dress code. Meanwhile, Sampras was all business on court. He projected a more serious attitude toward his tennis, in stark contrast to Agassi’s blasé approach. Their rivalry often felt like you were watching siblings on court: Sampras the elder, more responsible brother to the rebellious Andre. That they seemed so different to onlookers was precisely what made them such a fascinating pair. Still, Sampras-Agassi was more than just a battle of personalities. Each had his own distinct playing style. Pete had one of the greatest serves in the history of the sport, and Andre could make even the best of serves look elementary. Pete paired an intimidating wingspan at net, with a deft touch on his volleys, forming an impregnable defence of his side of the court. Agassi’s off-court flair was manifested in his groundstrokes; he became a wizard at taking the ball early and catching opponents off guard. One of his signature shots was the half-volley that he hit off a full swing from either wing. He brought new and exciting elements to the sport. When all these considerations are combined (on and off the tennis court), we get a fully formed understanding of why these two players were so compelling. Perhaps the most vital part was that they were American. That was the icing on the cake for the media, ATP, and fans to latch onto Sampras-Agassi for the long haul. I always felt that Andre looked a bit pressed when playing Pete, as if he had something to prove against his big brother. But, there was an added dimension to Andre’s anxiety: he knew that he had to make inroads on return if he wanted to win. Pete’s tremendous serve and volley game made it very difficult for opponents to break him. Even Andre, who is on a very short list of the game's greatest returners, had trouble in this department. Many times Andre would get to 0-40 on Pete’s serve only to have his advantage wiped away by aces. It must have been so demoralizing to know that your chances of winning were not always within your own control. The 1999 Wimbledon final is a perfect example of this – Andre played well, but there was no stopping Pete that day. One of the more surprising things I learned while writing this was that Sampras and Agassi played only two 5-set matches over the years. (Perhaps I was surprised because Federer and Nadal have contested five, including some of the most breathtaking tennis ever seen.) Yet, Nadal-Djokovic has featured only two 5-setters, and the same is true of Federer-Djokovic. So, going the distance isn’t necessarily the best indicator of a great rivalry, but rather the quality of the matches and how memorable they are. Sampras and Agassi just didn’t play that many iconic matches. The obvious choice is their 2001 U.S. Open quarterfinal, which Sampras won in four tie-break sets, with neither player losing serve. All who watched that match felt it deserved to be a final, and John McEnroe declared it some of the best tennis he’d ever seen. I’ll never forget Andre’s expressionless face afterward in the press room; he looked as though his spirit had been broken. When Pete and Andre played during the 90s, there was nothing on offer that could match their star power; the first order of business whenever a draw came out was to check if the two could meet in the final. They played so often on the biggest stages – 16 times in finals and 9 in Slams - that their rivalry was always in the spotlight. But, with all that has happened since, all the glorious tennis of the past decade, the Agassi-Sampras rivalry, unfairly, suffers in comparison. Just as Federer and Nadal cast a long shadow on Pete’s candidacy as greatest ever, so too they brushed aside Pete and Andre as the premier rivalry of the last 25 years. Spare a thought for them, because the Federer-Nadal rivalry has defied what we could reasonably expect from two athletes; it’s almost unfair to everybody else how godlike they’ve been.

Agassi and Sampras each did so much for the visibility and popularity of the sport, especially in the United States, that just having their names in a final was a huge draw. They have to be viewed beyond the lack of iconic 5-set matches featuring jaw-dropping rallies. Theirs was a rivalry that was a statement for American tennis, the marketability of the sport around the world, and the ability of two tennis stars to captivate the global consciousness. They set the tone for Federer, Nadal and Djokovic to truly make tennis a global sport. Even if, over time, Sampras-Agassi fades in our collective imagination, they will always be tennis royalty. This is the third in a series on great tennis rivalries: Steffi & Monica: Ill-Fated Rivalry & Story of What Might Have Been The Sisters Williams: Beyond Tennis Rivalry The story of Steffi Graf and Monica Seles is a complicated tale: a rivalry that promised to challenge Navratilova-Evert as one of the all-time duels, but failed to sustain the feverish pace of its first four years. I was shocked to discover that Steffi and Monica played each other only 15 times during their careers. If you think of women’s tennis between 1990 (Seles’ first Grand Slam) and 1999 (Graf’s retirement), these are the two women who commanded the public consciousness. Both dominated the tour for extended periods and were unquestionably the top two players by a wide margin. But, due to a pair of two-year stretches, one tragic and the other injury riddled, their rivalry never blossomed into what it ought to have been. Graf’s 22 Grand Slam singles titles dwarf Monica’s 9, and so it should be no surprise that Steffi holds a 10-5 advantage in their head-to-head. Makes sense, right? But this is the problem with assessing Seles’ place in tennis history: we can only speculate as to what she might have accomplished had her career not been interrupted. Consider too that the infamous stabbing was perpetrated by a Graf fanatic who sought to curtail Monica’s stranglehold on the game, one which she had successfully wrested from Steffi. Between 1991 and 1993, Seles won 8 of the 11 Slams she contested, a staggering return by anyone’s standard. She was at the absolute peak of her powers; none, including Graf, had answers for a blistering game that had transformed women’s tennis. Although Monica was without question the number one player during that span, Steffi still led their head-to-head up to 1993. The trouble for Graf was that Seles had been winning when it mattered most. Between 1990 and 1993, they met in 4 Slam finals with Monica winning 3, the only respite for Steffi coming on the lawns of Wimbledon in 1992. This is where their story turns tragic. For those who are unfamiliar with what transpired in Hamburg on April 30, 1993, this is a good starting point. The first tennis match I ever watched was the 1994 Wimbledon final between Martina Navratilova and Conchita Martinez. I had no idea who Monica Seles was, nor did I have any context for the gaping hole her absence from the tour created. As far as I knew, Steffi Graf and Arantxa Sanchez-Vicario were the top players. I was immediately drawn toward the Barcelona Bumblebee as the constant underdog clawing at Steffi’s throne. As for Monica, she was a foreign entity to me, an asterisk in the rankings; I knew nothing of the player she was prior to leaving the tour. Monica’s return in the summer of 1995, and her immediate success, was a stirring moment for the tour. I immediately thrust my support behind Seles to avenge Steffi’s many beatings of Arantxa. Seles made a triumphant return to the WTA at the 1995 Canadian Open. She followed that with a run to the U.S Open final, galvanizing support from Americans who were attuned to her story; she was an underdog for the first time in her career. That Seles would meet Graf in that final only added to the drama of the match. Consider too, for some tennis fans, Graf was now the villain; the stabbing was carried out in her name. All these factors resulted in a mouth-watering final, which Steffi won in three sets. Still, Seles was back, and her victory at the subsequent Australian Open in 1996 appeared to breathe new life into a once stalled rivalry. Watch Monica Seles reflect on 1993 and the 1995 U.S. Open final against Graf. After Seles’ comeback in 1995, she managed a further four Slam finals, with that solitary win at the ’96 Australian Open. Simply put, she was never quite the same player. A very good player, but nowhere near the dominant force that blitzed the tour in the early ’90s. Meanwhile, Steffi was in the twilight of her career. Between 1997 and 1999, she missed four Grand Slams and countless months due to injury. The window had closed for the two to reignite their rivalry. They played five times after Seles’ return with Graf winning all but one encounter, the 1999 Australian Open quarter-final, after Steffi had missed the previous Wimbledon and U.S. Open.

Who’s the best comparison we can make to Monica’s still excellent second career? Mary Pierce (2 Slams, 6 finals, 14 QFs) or Jana Novotna (1 Slam, 4 finals, 22 QFs)? Neither woman advanced to the final 8 with the same regularity as Monica. Between 1995 and 2003, Seles reached 20 Grand Slam quarterfinals from 26 attempts. That’s a staggering level of consistency for which most current players would sell their souls. Consider that Kim Clijsters reached 19 quarterfinals in her entire career. While Seles didn’t win as much upon her return, she still had plenty of game, which was reflected in her results. Due to one crazed man’s overzealousness, Monica Seles suffered a physical and mental ordeal that changed her life and tennis history. Sport fans never got to see the Graf/Seles rivalry play out organically, one which promised so much but yielded a measly 15 meetings. The stabbing in Germany also altered the discourse surrounding both players’ careers. Monica – who was robbed of the chance to become one of the all-time greats – became an irresistible darling of tennis fan. Meanwhile, Steffi will always have her record questioned by fans and pundits. How do her 22 Slams hold up against Serena’s 17, when Seles might have lopped a few off Graf’s tally? Perhaps Steffi may have made adjustments to thwart Seles at her peak, winning everything anyway. But, now we will never know; Steffi’s legacy will always have that cloud hanging over it. Aside from their individual suffering, the biggest shame is that tennis fans and tennis history were cheated of something truly special. This is the second in a series on great tennis rivalries: The Sisters Williams: Beyond Tennis Rivalry. So much has already been written about the Williams sisters over the past decade that it’s difficult to add anything useful to the discourse surrounding their importance to the game of tennis. As individuals, each stands out for their own accomplishments. Serena Williams is already one of the top four best women ever to have wielded a racquet. By the time she retires, she may well be the undisputed best. Elder sister Venus has nurtured her to this point. Throughout their parallel careers, Venus has served the dual roles of trailblazer for and biggest supporter of her younger sister, all the while carving out her own legacy amongst a rich tapestry of tennis legends.

Serena was first to burst through the Grand Slam gate with her win against Martina Hingis at the 1999 U.S. Open, but it was Venus who led the Williams’ charge to #1 by the early 2000s. At the start of 2002, the WTA was squarely Venus’ domain. Fresh off back-to-back Wimbledon and U.S. Open titles, Venus seemed poised to dominate for years to come. However, Serena upset that narrative by winning Grand Slams two through five as part of her now famous “Serena Slam.” Those who felt sorry for Serena while Venus shone brightly now bled for big sis. Either way, both had arrived. Their rivalry is punctuated by so many unique considerations. They are sisters, competing against and with each other, winning more often than not. The thing about the “Serena Slam” that is often overlooked is that Serena played Venus in each of those finals. For me, that is one of the most amazing parts of their story. The tennis world was gifted these two supremely talented sisters who ruled the sport at the same time, but that which happens in our backyards, happened for them on the grandest world stages. Their grace in navigating that sibling dynamic at such young ages will always mesmerise me. Can you imagine having the joy of reaching #1 in the world being tempered by having unseated your sister in the process? These are the types of things that Venus and Serena dealt with that we will never understand. Theirs is a unique dynamic. Tennis players have rabid fan bases; Venus and Serena are no stranger to this phenomenon. Perhaps, because of their distinct celebrity and achievements, they have even larger and broader followings than most. The flip-side of this is that they have detractors who foster a keen dislike of the two. Some dismiss them as “haters.” Others view it as a tale-as-old-as-time misogyny that undercuts successful, strong women. Some of it is understandable, a push back against larger-than-life personalities which exist outside our realm of understanding. However, the resistance is also racial. Because racism is often ambiguous and not easily identifiable, some make the mistake of dismissing it from the discourse surrounding the two. The ugliness of Indian Wells in 2001 is at the forefront of this discourse. There was also the Irina Spirlea bump at the 1997 U.S. Open, where the Romanian intentionally bumped Venus on a changeover, and later declared “she thinks she’s the fucking Venus Williams.” But, as is the case with most incidents of racism, they are difficult to pinpoint. We know Venus and Serena have dealt with this throughout their careers, but we have no way of knowing the full extent of it. To their immense credit, they have handled most of the obstacles that could have derailed their success with remarkable aplomb. Tennis statistics will never hail the Williams rivalry as one of the all-time greats. Yet, their careers are prime examples of how numbers often obscure context in favour of wins and losses. How much weight should we attribute to the “unique considerations” that have shadowed them throughout their time on the WTA Tour? It’s not something that can be fully assessed. Instead, we should marvel at all that they have been able to achieve collectively: as rival singles players, as a doubles tandem, as a sibling rivalry, as friends, and as world class athletes. With the best of their rivalry almost certainly behind them, it’s time to heap as much praise on them in appreciation of careers that we will never see the likes of again. This is the first of a series that will focus on some of the best tennis rivalries. Serena Williams crashed out of the Family Circle Cup today, falling 4-6 4-6 to Jana Cepelova. Fighting an injury that required a visit from the trainer early in the second set, Serena was unable to overcome her feisty, consistent opponent. This was not the start I imagine Nike envisioned for Serena’s new tennis kit, a sharp black and gray number. In her post-match presser, Serena pointed to fatigue and an impossible schedule over the last two years that have finally left her needing a break from the tour. For Serena's thoughts after the match, click here. Venus also threatened an early exit, before rallying to take her match 6-3 0-6 7-5. Vee had been fighting a bug that limited her movement in the second set, suffering a bagel at the hands of Barbora Zahlavova Strycova. Having fought her way through to the finish line, the draw is now wide open for Venus to continue her remarkable return to form in 2014. Eugenie Bouchard awaits her in the 3rd round. Pam Shriver had some choice words about Serena's shock loss today: I'm not sure exactly what Pam was trying to say here. Perhaps she was trying to make a case for giving the spotlight to some of the younger players on tour? Whatever the intent, it was a certain misstep from the tennis veteran. It came off as a personal slight against Serena, and petty. These WTA tournaments survive because of the star power of players like Serena and Venus showing up and making deep runs. Does the paying public in Charleston want to see a Cepelova/Tomljanovic final? There's a fine balance to be struck in the give and take between developing new talent and the survival of the WTA Tour on the backs of its established stars. I'd love for Pam to clarify what she meant by the tweet.

Cricket has played a very important role in my life; I’ve even written a Masters thesis on West Indies Cricket and Colonialism. Brian Lara is my all-time favourite. Messiah, Pariah, he played many roles during his career. The one constant through it all was his genius. Many have had questions about his character and commitment, but NEVER his talent.

I am currently working on a more extensive piece on Lara, but in the interim, here’s arguably his greatest work. This innings against Australia came at one of the most tumultuous times in his career, 153* to steal an improbable win for West Indies. He was the Messiah that day. Watch that cover drive at 0:18 off Glenn McGrath, breathtaking. So happy for Mao Asada and Carolina Kostner! After a shocking short program in Sochi that knocked her out of medal contention, Mao rebounded to capture gold at the World Figure Skating Championships. Meanwhile, Carolina Kostner matched her Sochi bronze medal showing, finishing just behind Yulia Lipnitskaya.

Mao’s indicated she might retire after these World Championships, but hasn’t seemed to definitively make up her mind. Her short program, in which she landed a triple axel, broke Yuna Kim’s world record from Vancouver 2010. For Kostner, this was her last competitive skate. Should this be the last time we see both women on the international stage, they both went out in style! West Indies stomped all over Pakistan today to reach the semis of the T20 World Cup. Pakistan were in control after restricting the defending champs to 84/5 from the first 15 overs, then it all fell apart. West Indies pummelled them to the tune of 82 from the last five and 59 from the last three overs.

West Indies had many heroes today. Bravo and Sammy disfigured the typically reliable Umar Gul and Saeed Ajmal, while Samuel Badree and Sunil Narine laid further claim to being the best spin duo in the shortest format. They were aided by Denesh Ramdin who facilitated four stumpings to run through the middle of Pakistan’s batting. Set 167 to win, Pakistan folded for a paltry 82. On to the last four where West Indies will face Sri Lanka in a rematch of the last T20 World Cup final. South Africa and India will contest the other semi-final. Match analysis here |

ARCHIVES

September 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed