Tina Thompson (left) Sheryl Swoopes (centre) Cynthia Cooper (right). Photo credit: AP/Brett Coomer Tina Thompson (left) Sheryl Swoopes (centre) Cynthia Cooper (right). Photo credit: AP/Brett Coomer Tina Thompson's imminent retirement from the WNBA will officially mark the end of an era for women's sport. Thompson is the last remaining member of the class of players from the inaugural season of 1997. She will retire as the league's all-time leading scorer and second behind Lisa Leslie in rebounds. Hers is a career of remarkable longevity, having emerged from the shadows of Cythia Cooper and Sheryl Swoopes to become a star in her own right. She will most likely be remembered as one-third of the trailblazing trio of Houston Comets who captivated audiences while winning the first four WNBA titles. The first draft pick in WNBA history, Thompson is also the only woman to play in each of the 17 seasons since the league's inception.

Although the WNBA has had its share of stars in Thompson, Swoopes, Cooper and Leslie, it has long suffered from sporadic media coverage. I remember tuning into SportsCenter to find out the score of a 2005 WNBA Finals game; I had to wait until the second half of the telecast before getting a brief recap of the Sacramento Monarch's championship clinching win. I was bowled over that a major professional sports team got only a footnote after winning a title. In my eyes, this firmly situated the lowly position of women's professional sport within the overall superstructure of a male-dominated culture. My outrage at ESPN's coverage was often met by the usual chauvinistic replies: the women aren't as good, their brand of basketball is inferior, nobody wants to watch that. I've always felt that ESPN had a cultural responsibility to help mould the way men view women's sport. To my mind, even if ratings demanded otherwise, ESPN should have run that story at the top of the show. Money, money, money - I know. At the risk of sounding cliché, sometimes there are things more important than the almighty dollar, even when trying to run a successful business. What would have been ESPNs net loss for moving up the story and giving it a bit more airtime? Obviously, I don't have the answer to that question, but it seemed to me like a major missed opportunity to make a statement about the network's commitment to the advancement of women's professional sport.

0 Comments

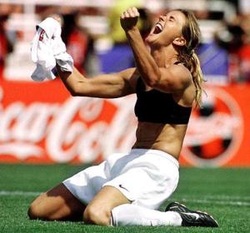

It’s a pleasure to introduce my first guest post courtesy of Toni Rogers (@MzRogersHood). A life-long athlete and current sport administrator in college athletics, she offers a critique on how issues of gender and sexuality complicate the sporting experience for female athletes. I am a product of the “Girls of Summer.” The memory of the 1999 Women’s World Cup Final has left a lasting imprint in my mind, from the oft forgotten blocked penalty kick by Brianna Scurry, to the infamous shirtless celebration of Brandi Chastain and the hero that was Mia Hamm. My life has always been, and continues to be, consumed by sport; it is the one thing that has the ability to fill me with me complete joy, but also the power to overwhelm and frustrate. Mia Hamm and company had throttled themselves to the forefront of American sporting culture by the late 1990s, unlocking opportunities for young girls like me. Yet fifteen years later, the progress that female athletes have made is questionable.  Brandi Chastain. (Photo credit: Atkins/AP) Brandi Chastain. (Photo credit: Atkins/AP) Years ago, I idolized the beauty, grace, and poise that Hamm possessed. She was a marketer’s dream. Hamm was the “girl next door”: she was well spoken, talented, and importantly, had a pretty face. Still, a part of me was always instinctively drawn to goalkeeper Brianna Scurry. Her intensity was unlike anything I had seen. She made no apologies for her fierceness on the field or her failure to smile. At the time, I couldn’t understand why posters of Scurry were so hard to find, while my friends’ walls were littered with pictures of Hamm, Chastain, and Julie Foudy. After my many years spent as a player, coach and now administrator in athletics, the answer has become increasingly clear, but no easier to accept. The answer lies in the reasons my Little Tykes soccer team had to be named the “Queen Bees” rather than the “Killer Bees,” and why I found myself defending my own sexuality before I even truly understood it.  Brianna Scurry. (Photo credit: Shaun Botterill/Getty Images Sport) Brianna Scurry. (Photo credit: Shaun Botterill/Getty Images Sport) Women who possess the traditional norms of feminine beauty and behavior are thrust to the forefront of their sports. Since the emergence of Title IX, women have had an increasingly greater presence in athletics, whether at the grassroots level or in the professional realm. It is no longer uncommon to see women’s games on ESPN or other major networks, and some female athletes have become national (even global) sensations. But coupled with this presence is a trend in how the media and sporting culture choose to market and represent women’s sports.

Photo credit: www.usopen.org | Tornado (left) poses with the runner-up trophy after the 2013 U.S. Open Junior Final. Photo credit: www.usopen.org | Tornado (left) poses with the runner-up trophy after the 2013 U.S. Open Junior Final. In my U.S. Open wrap-up I noted that we’re “seeing the legacy of the Williams sisters in Stephens, Duval and the promising Taylor Townsend.” Further evidence of this is the aspiring careers of Tornado and Hurricane Black. It’s no accident that we’re witnessing a proliferation of young black tennis players in the women’s ranks - the seeds sown by the Williams family are coming to bear. Yesterday, espnW published an article profiling the Black family and the rise of daughters Tornado and Hurricane. After having supported the eldest sibling’s (Nicole) aborted tennis career, parents Gayal and Sly fashioned a similar path for their youngest daughters. It’s virtually impossible to believe that the Blacks went about this without Venus and Serena as the blueprint, yet the family seems to distance themselves from the legendary siblings at every turn: "We’re always going to be compared, but we’re the Black sisters not the Williams sisters," Gayal said. "We’re going our own way. We played the junior ITF circuit, the Williamses didn’t. It’s nice [for Tornado] to be compared to Serena, who’s the greatest of all time, but they want a name for themselves and I think they’ll live up to their own names and win their own Grand Slam titles in years to come." Tornado may want to have a career for herself because her parents have probably programmed her to say so. Make no mistake, this has nothing to do with what the tennis sisters want for themselves and everything to do with the careful orchestration of their parents. "Alicia got her name ‘Tornado’ when she was 3 and playing out of her mind," she said. "We couldn’t believe how amazing she was and we knew then we had a champion. When the next one was born, we knew she could do it, too, and so her [legal] name is Tyra Hurricane." What does it look like for a 3-year old to be playing out of her mind? Surely Tornado exhibited exceptional skills at a young age, but this kind of hyperbole speaks more to the overzealousness of the parents than it does to any prodigious skill shown by the toddler. It also doesn’t help when Gayal refers to Hurricane as “when the next one was born” - the next what? Breadwinner? Commodity? This is not a case of a parent recognizing aptitude as a child develops and then nurturing that interest. In this instance, there is a seedy overtone that is quite typical of the tennis parent/prodigy relationship - certainly not the first time we’ve seen a family apply such rigid control to a child’s career. The Blacks find themselves trying to do it in a different age for tennis prodigies - gone are the days when adolescent players ruled the tennis world. They rightly point out that they have chosen a different route than the Williams family by playing the junior circuit etc., but they are handcuffed into doing so by a sport that is wholly different today than it was 15 years ago when Martina Hingis toyed with the WTA as a 16-year old. Venus and Serena could overpower a large majority of the WTA tour at that age, but the power game of today requires a lot more physical development and nurturing - both of which require a lot more money. This is where the unique names of the young women factor into the equation: "It’s great for everybody, for publicity. Greg Norman was the Great White Shark. Sir Richard Branson said you have to have a brand to use. We don’t want them to be the next Williams sisters or those African-American sisters. They’re Tornado and Hurricane so people can identify them as something other than the next Venus and Serena. And what better marquee above the US Open than ‘Tornado and Hurricane Black?’" It is the intricate branding of the girls - even from before they were born - that positions them as commodities. It makes for a good story when a parent can predict greatness for a child from an early age and have it actually happen. Many thought Richard Williams was a loon for Venus and Serena’s unorthodox tennis upbringing, but he is now celebrated as a visionary. How often does this story have a happy ending as opposed to disintegrating into a cautionary tale? The Blacks’ narrative of how they planned for this fairytale success borrows from what we’ve already seen with Venus and Serena, but what are the chances that lightning can strike twice and so soon? While the ESPN piece paints a favourable picture of Sly and Gayal, there is evidence to suggest their parenting is a bit more erratic than was neatly bundled in that story. Responding to a WSJ pieceaddressing Taylor Townsend’s tiff with the USTA last year, Gayal took to the comments section to separate her daughter from Townsend and vociferously side with Patrick McEnroe and the USTA: As the mother of Tornado Black, Hurricane Black and former player Nicole Pitts (now in medical school). Patrick, Jose and Olga are all doing a great job running the player development program. She adds: Tornado is in the same training program as Taylor and has to abide by the same rules. Tornado also received the same letter warning her about her fitness as did all full time students at usta. Tornado is also black and has a full body of muscle. But Tornado watches her diet, runs on the beach and does extra fitness to meet the guidelines of fitness by the USTA. Why should the rest of the players have to abide by the rules and NOT TAYLOR TOWNSEND!!! Rather than show some solidarity with Townsend, Gayal takes the opportunity to praise Tornado’s dedication and simultaneously throw Taylor under the bus by questioning her work ethic. Not only was this terribly opportunistic and in poor taste, but also unsettlingly aggressive toward a young girl who presumably shares the same aspirations as her own daughters. It also dehumanized Townsend who, as an adolescent, was presumably experiencing all the awful growing pains that everyone goes through at that time in life - particularly young women. This was expressed quite vocally in the article by Martina Navratilova and Lindsay Davenport, who both decried the gross insensitivity on the part of the USTA. Just as alarming was Gayal’s effusive praise of the USTA and McEnroe: Hats off to the USTA PLAYER DEVELOPEMENT for doing a great job with all the up and coming juniors. Because of your great rules and training is why everyone is begging to come to Boca Raton and train now with the best of the best in UNITED STATES!!! If you don’t like the rules?? LEAVE OR DON’T COME!!!!! Perhaps this was the Blacks’ way of jockeying for more funding from the USTA should Townsend no longer be a part of the program? Whatever the motivation, it was an embarrassing display - although it did make for some juicy reading. I encourage everyone to read through all the comments and see the responses to Gayal’s posts. *This article is written under the assumption that those comments were in fact from Gayal Black and not from a master puppeteer in search of the next great tennis drama. As for Tornado Black, recent runner-up at the U.S. Open Juniors (an event not contested by Taylor Townsend who retired from junior competition), she rightly views Serena as the gold standard. Still, she clings to the family mantra that separates her and Hurricane from the Williams sisters at all costs: I want to be myself and not Serena or Sloane. I want to focus on me right now. Perhaps there is merit to the argument that the Blacks need to separate themselves from the Williams clan in order to secure sponsorship etc., but the comparison is something they will have to accept if the girls are to become as great as their parents expect them to. The only way they will be known in their own right is if they eclipse the record-breaking achievements of their trailblazers - not likely to say the least. In the meantime, they better get more comfortable with the idea of playing in their lengthy shadows. That they are an embodiment of the Williams sisters’ legacy is something to be proud of. Perhaps the most striking takeaway from their story (thus far) is a better understanding of just how good a job Richard and Oracene Williams did with raising Venus and Serena.

Authors note: special thanks to @ElliottJMR and Courtney Nguyen (@FortyDeuceTwits) who brought both articles to my attention via their tweets! Everyone knows about Roger Federer’s record 17 Grand Slam titles, but what else can we learn from looking a bit more closely at his overall record in majors? Being a bit of a tennis nerd, one of my favourite things to do is study graphics like the one below; they often appear on a player’s Wikipedia page. What we already know:

Digging a little deeper:

There’s no arguing that Roger Federer is still the best to have ever played men’s tennis. Whether that will remain the case has been a matter of great debate. He may recover from his recent struggles and add to his tally of 17 titles, making Nadal’s chase more difficult. Nadal might encounter more injuries or Djokovic could go on a Federer-esque tear the next few years. Amidst all the uncertainty, Federer’s career thus far is the stuff of legend. Even if you feel, as I do, that many of his titles came at a time when men’s tennis was not at its deepest, the absurd consistency is jaw-dropping. Many of his records will never be eclipsed — even if another player ends up with more majors. |

ARCHIVES

September 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed